In this chapter, I start by recapitulating the interventions proposed in the two preceding chapters, and then discuss some typical counterarguments against such interventions—or Buddhist-Stoic training in general. Then, as a final class of interventions, I discuss the development of positive attitudes towards mental phenomena. Instead of observing the world as it is and learning from it, here the emphasis is on actively cultivating certain ways of relating with the world that reduce negative feelings (valence). This approach is “positive” compared to the training based on various kinds of reduction emphasized in the preceding chapters. Acceptance and letting go are the key attitudes here; it turns out that they are intimately related to the reduction of desires and expectations. In fact, letting go, which I interpret as a form of relaxation, can be seen as a principle that unifies most of the training methods described in this book.

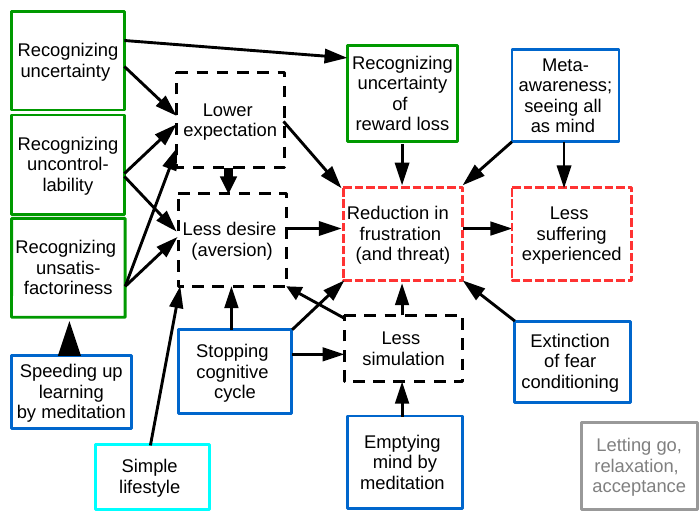

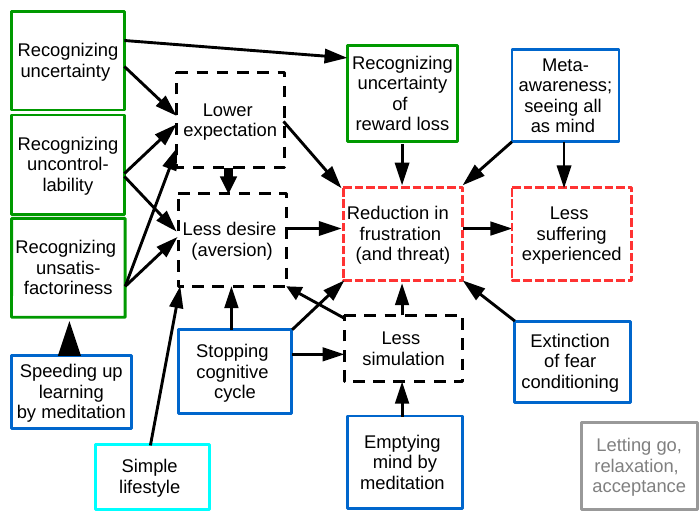

The flowchart in Fig. 18.1 recapitulates the main mechanisms of the different interventions described in the two preceding chapters, while briefly mentioning some to be explained below. The most fundamental interventions are recognizing uncertainty, uncontrollability, and unsatisfactoriness (green boxes on the left). These lead to reduction of expectations and reduction of desire, including aversion (black dashed boxes), which reduce the frustration computed and suffering experienced (red dashed boxes). A simple lifestyle (bottom left) is another intervention that I did not describe in much detail in this book, but it is also a well-known method for reducing desires. Another related intervention is recognizing the uncertainty of perception and in particular the perception of reward loss (green box, top middle), which reduces the computed frustration as well.

Mindfulness meditation strengthens and speeds up many of the interventions just mentioned, which is depicted as a blue box at the bottom left-hand corner. Meditation also brings several new mechanisms into play; some are shown as separate blue boxes in the chart, although in practice, they all come from the same intervention. First, meditation tends to make the mind empty, thus reducing simulated frustration (third column, two boxes at the bottom). Meditation also enables stopping the cognitive cycle or chain (Fig. 15.2), which goes from perception to desire and frustration (blue box in the second column). Such stopping can have many different effects, but what is emphasized here is that it can directly reduce desire as well as simulation, while it can also explicitly prevent the frustration computation itself. Another intervention offered by meditation is that it creates a form of metacognition and meta-awareness (blue box at the upper left-hand corner), which may eventually lead to the attitude that all phenomena are just in the mind, as proposed by Mahayana Buddhist philosophy, thus directly reducing all kinds of suffering.

All the interventions just described are intimately related to manipulating terms in the frustration equation (🡽). (Those that reduce desire are a bit more indirectly related since they essentially prevent the mechanism in that equation from being triggered at all.) However, we also saw some interventions related to meditation that work in very different ways. Meditation is actually a highly complex phenomenon, and it certainly has many effects mentioned only briefly, if at all, in this book. The flowchart lists as a further example the extinction of fear conditioning; recognizing the emptiness of categories could also have been added. The flowchart has a further box on letting go and acceptance, which will be treated later in this chapter.

Essentially, these interventions reduce frustration (red box in the middle). Threat computation is reduced as well since threat is based on predicted frustration. Finally, this reduction of frustration and threat reduces the conscious experience of suffering, or mental pain. Meta-awareness is very special in the sense that it can directly reduce conscious suffering even if the frustration or threat computations are performed, which is indicated by the direct arrow from meta-awareness to conscious suffering.

Let us next consider a typical objection that can be raised at this point: the thinking underlying the interventions of the preceding chapters seems depressing. One may ask whether not wanting anything and not expecting much leads to complete inactivity and, indeed, to some kind of depression. A diagnostic criterion of depression is “markedly diminished interest (...) in all, or almost all, activities”,1 which sounds a bit like having substantially reduced reward expectations and having few desires. The fundamental question is: Can such reduction of desires and expectations go too far?

Let us consider first how much expectations should be lowered. Is it enough to admit the actual levels of uncertainty and uncontrollability, or should we go further and consider things even more uncertain and uncontrollable than they really are, thus lowering expectations even more? If our only goal were to reduce suffering in the agent, we could simply program it to assume that everything is completely uncertain and completely uncontrollable. Then, the agent would expect zero reward, or very little, in any state or from any action. As a consequence, it would have virtually no desires either. Is this a good way of programming an agent?2

Claiming that Buddhist training can lead to something akin to depression is, in fact, a well-known point of criticism, and similar arguments have actually been raised against Buddhism throughout its history. I think such criticism is not very relevant because it considers an extreme case, which is unlikely to be achieved by most people practicing such systems. Perhaps the point is that most people living in a modern industrialized society simply have too many desires, and it would be better for them to have fewer of them. This would explain why people engaged in Buddhist training tend to get happier when they reduce reward expectations. It may be irrelevant to ask what might happen in the extreme case where they completely annihilate all their desires—which is a feat even most meditation masters are incapable of. Buddhist philosophy actually emphasizes the general principle of the “middle way”, or moderation, which sounds like a good idea here as well. The situation might be different for Buddhist monks or nuns engaged in full-time practice for many years, but they follow a very special lifestyle, which is specifically designed to be compatible with having very few desires.3

On the other hand, there is certainly something fundamentally different between a depressive state and a mental state where the unsatisfactoriness of the world is seen from a Buddhist perspective. If an agent concludes that none of its desires are going to be fulfilled and it will never receive any reward, that gives in itself no reason for a negative feeling or valence. The agent would just rationally decide that no desires are worth pursuing, it would not engage in goal-oriented action, it would predict zero rewards in the future, and, consequently, it would suffer less since there is no frustration.

If humans tend to get a negative feeling after seeing that the world is fundamentally unsatisfactory, it must be because there is another “higher-order” desire, presumably coming from the self-evaluation system treated in Chapter 6. A depressed person, in particular, finds the very unsatisfactoriness of the world frustrating, and wants to find satisfaction or reward in various kinds of seemingly pleasurable objects and activities. In our framework, we would say that she is frustrated in terms of her self-evaluation, as she sees that she gets less reward in the long run than she “should” according to some internal standard (possibly based on social comparison). The self-evaluation system may indeed conclude—based on a superficial calculation—that since no goals can be reached and no reward can be obtained, there must be something wrong with the agent. Thus, a negative meta-learning signal is generated, and this would be felt as suffering.

However, I think an important point in the Buddhist philosophy of unsatisfactoriness is that if the self-evaluation system sends a negative signal when the agent does not get enough rewards, the system is simply malfunctioning. Clearly, the realization of the total unsatisfactoriness of everything should also influence the self-evaluation system. The self-evaluation system should set its expectations and its standard of an “acceptable” reward level very low, even zero. The self-evaluation system cannot rationally claim that the agent is not getting enough rewards if the system itself believes that no rewards can possibly be obtained! As such, Buddhist philosophy proposes that there is no need to be frustrated about any long-term lack of reward, nor is there any need to make any negative self-evaluation; not getting much reward and not reaching one’s goals is natural and unavoidable.

Another objection that could be raised against the philosophy presented here is that it may not be useful to reduce frustration since the frustration signal is useful for learning. Human beings seem to be trapped in a situation where they need frustration to learn, while they suffer from it. That may sound like a dilemma with no satisfactory solution. However, I’m not sure there is any serious dilemma here. One reason is that, as discussed in Chapter 5, many of the rewards we are programmed to receive are actually rather useless “evolutionary obsessions”; frustrating them may not teach us anything useful, if it is not the very futility of those rewards. The same is true from the viewpoint of insatiability: why should one try to learn how to better satisfy desires that cannot be satiated anyway?

Furthermore, Chapter 14 proposed that a large part of the problem is how frustration is made conscious even though it need not be; learning from frustration could, in principle, happen on an unconscious level. It might seem that not much can be done about this, but in fact, an intervention is possible, as was seen in the discussion on meta-awareness in Chapter 17.

Likewise, it might be claimed that thinking about threats is useful since then, the agent learns to avoid them. However, people worry about horrible things which are extremely unlikely to happen; they also worry about things which are unavoidable, such as death. Such worrying is unlikely to improve the performance of the agent at all. It may actually decrease the performance since so much energy is spent on those rather useless computations.

Yet another counterargument is that while understanding the uncertainty of all perceptions reduces frustration, it may actually improve learning and make us more “intelligent”. Uncertainty and uncontrollability are real properties of the world, but we may have been grossly underestimating them.4 Thus, learning to better appreciate uncertainty and uncontrollability is a useful meta-learning process, even from the viewpoint of trying to optimize rewards in the world.

Based on these counterarguments, I think that while it may be meaningful to claim that not all frustration should be removed, most of it can still be removed without making learning or the ensuing behavior any worse.5

Some readers may still not be convinced. They might argue that desires feel good; without them, life would be empty; besides, they have no time or energy for the training described in this book. I think it is important to understand that this book is fundamentally an exposition of a scientific theory. A scientific theory per se does not tell you what to do. It only tells you that if you do X, then Y will follow (with some probability); it explains causal connections and, in particular, what effects different interventions will have. As such, it is up to you to decide which interventions, if any, are actually worth it for you. It depends on your preferences or your values (in the ordinary sense of the word), and no scientific theory can tell you what to do without considering your personal preferences. The interventions have side-effects or costs, and the cost-benefit analysis is different for each individual and intervention. One individual may get a lot of satisfaction from pursuing and achieving a certain goal, while another might get much less; for some other goal, it might be the other way around. Likewise, how much an individual benefits from a particular intervention must vary from one individual to another. Ideally, some scientific analysis of your personality, temperament and lifestyle might be able to tell which interventions are the best for you, but we are not there yet.

Some of the arguments against Buddhist-Stoic training may be due to the simple fact that reducing anything sounds like a negative thing, as if you were missing out on something. Next, I will try to give more positive interpretations of the reduction—or even absence—of desires and expectations.

To begin with, the absence of desires can be expressed as contentment, in the literal meaning of being content with what one has and not wanting more. The insatiability of desires, in particular, implies that a simple-minded agent cannot be content: it always has to search for more rewards, leading to endless frustration. If an agent has no desires, we can, from a positive viewpoint, consider it to be content with the current situation.

If contentment becomes strong enough, it may turn into a feeling of gratitude. Gratitude training or meditation is a major topic in itself, and there are specific methods to increase gratitude. Gratitude is an emotion that is social or interpersonal, which is why it is a bit outside of the theory of this book. In any case, the paradox of gratitude is that it actually enhances the well-being of the person being grateful—not only of the person to whom the gratitude is directed. As Seneca puts it:

I am grateful, not in order that my neighbour, provoked by the earlier act of kindness, may be more ready to benefit me, but simply in order that I may perform a most pleasant and beautiful act; I feel grateful, not because it profits me, but because it pleases me.6

An even more fundamental positive interpretation of having no desires is freedom. While an emphasis on freedom is ubiquitous in Buddhism, Epictetus summarizes the idea in a way that is, yet again, in complete harmony with the Buddha’s philosophy:

Freedom is acquired not by the full possession of the things which are desired,

but by removing the desire.7

More generally speaking, the condition of a human being has been described as being a “puppet of the gods” by Plato,8 meaning that “affections in us are like cords and strings, which pull us different and opposite ways”. We have to remove those cords and strings if we want to be free. Instead of being enslaved by our neural networks with their interrupts and unconscious action tendencies, we need to liberate ourselves from such evolutionary constraints, giving more space for conscious deliberation and the use of reason.

Another positive attitude that is fundamental in meditation practice is acceptance. There is, in fact, an important caveat in any attempt to reduce mental phenomena, be it desires or wandering thoughts. It is important that this training does not lead to the idea or evaluation that the mental phenomena are somehow bad. Such an attitude would, in itself, easily lead to aversion and thus, to suffering. In the extreme case, if there is aversion towards the mental phenomenon of aversion, that may lead to a vicious circle, which constantly increases aversion. To counter this tendency, it may be necessary to actively create new mental phenomena so as to neutralize the existing ones.

It may sound paradoxical to say that one should not think of the mental phenomena as bad, or at least undesirable. How could one not think that, say, desires are bad if one believes they lead to suffering? And how is one supposed to get rid of them if one does not regard them as something negative, something to be avoided?

The solution to this paradox is that while the actions of the meditator should be chosen so as to reduce desires (or other mental phenomena), it is still possible to avoid creating any new aversion in the sense of a new mental process. Thus, on an abstract level, it is useful to consider the desires “bad”, or perhaps rather as something that it would be better not to have, but such thoughts should just work in the background as weakly as possible, instead of being strong and actively cultivated. In particular, they should not lead to any interrupt-like aversive emotions. Such processing is possible since the neural networks can implement automated habit-like action tendencies that try to avoid certain phenomena, and that can happen without any need to activate the desire/aversion system. As an extreme example, when you are walking, you know that losing your balance is “bad”, but you probably don’t feel a constant aversion or fear towards stumbling; your neural networks have simply been trained to avoid that happening; they “reduce stumbling” so to say but without any aversion.

In practice, it has been found that with meditation, the tendency to develop aversion is so strong that specific techniques are necessary to reduce it. The key technique is to cultivate the attitude of acceptance. This means a general attitude of accepting all thoughts and sensations that come to the mind, instead of resisting or judging them. More precisely, acceptance here means simply not activating processes of aversion, i.e. not activating a desire to get rid of something. So, acceptance here is taken in a very limited sense: this is neither about moral acceptance nor about thinking that some things could not be bad for you. Such acceptance could also be described as removing resistance; nonreactivity is a related term used in current research.9 For example, a depressed person may be annoyed by the very occurrence of rumination. In such a case, accepting the fact that rumination occurs may actually be beneficial, since it removes the suffering due to the aversion to rumination.10 Again, acceptance does not here mean that the person would give up any techniques that reduce the rumination.

An accepting meta-cognitive attitude can actually be adopted towards all mental phenomena. Many mental training systems include some kind of active acceptance practice of all mental phenomena as an integral part. An acceptance practice can be seen as a specific method for reducing aversions of all kinds. It complements the methods described in the preceding chapters, which were more oriented towards reducing desires in the restricted sense of the word (i.e., excluding aversion). It is closely related to the practice of letting go, which will be considered below.11

Theories such as those explained in this book may help in the acceptance training because simply understanding the mechanisms behind, say, wandering thoughts or emotions may enable you to accept them. Suppose you are convinced that they are natural processes, which even have some computational benefits, and that they are largely outside of conscious control. In that case, it may be easier to just let them happen and go away naturally, without fighting against them. This is related to seeing “causality” in the Buddhist sense of the word (considered in Chapter 16, see 🡽), but it goes further since the phenomena are seen as not only natural and uncontrollable but even useful—at least from an evolutionary viewpoint. Based on this viewpoint, even failures and errors could be accepted as an unavoidable part of a learning process, or of life; it is not necessary to get upset by them and activate the brain’s pain system.

Ultimately, even the feelings of pain and suffering themselves need to be accepted on some level. Any aversion towards them will create a lot more suffering. As an extreme example, people suffering from chronic pain will suffer even more if they “catastrophize” the pain, resist it, and develop a particularly negative attitude towards it; accepting the pain will help.12 The Buddha gave a famous simile of a man who is struck by an arrow, which inflicts physical pain. If the man “sorrows, grieves, and laments”, feeling aversion towards pain, he makes the suffering even worse, as if he were struck by a “second arrow”.13

Buddhist philosophers often use the concept of “letting go” to recapitulate the general attitude that underlies the mental training described in this book. At the most concrete level, the idea is that we let go of things and objects in the sense that we don’t strive to possess or control them anymore. On a more computational level it means we let go of desire, i.e. we don’t even want those things in the first place—nor do we want to avoid them. The same approach can further be applied to thoughts and perceptions, which are understood to be subjective and unreliable, so they can be let go of. Feelings and emotions are likewise just observed and then let go of. The whole simulation called consciousness is no longer taken that seriously. Combined with the no-self philosophy, the attitude can be recapitulated as letting go of everything that is not part of me, and since nothing really is part of me, or my “self”, everything is let go of.14

Letting go is an expression that obviously has a clear connection to the term “reduction” that we have used very often. It is not so much a question of programming new routines or new functionalities. The idea is to reduce activity, letting go of existing mental associations and routines. The key is less desire and aversion, less replay and planning, fewer interrupts, and so on.15

An important point about letting go is that it circumvents the paradox of wanting not to want anything. If meditators want to reduce desires, they can be seen as wanting not to want, which may sound impossible. This apparent paradox in Buddhist philosophy has been pointed out by a number of authors: since wanting not to want is a form of wanting, how could one possibly get rid of wanting by such wanting? The paradox is actually so obvious that even the Buddha himself, as well as his immediate disciples, were confronted with claims that his system is inherently paradoxical.16 Thinking of the mental process in Buddhist training as letting go, and as reduction, should largely resolve this paradox of seemingly wanting not to want. The term “letting go” describes a reprogramming that reduces mental activity instead of introducing a new desire.

One way of interpreting letting go is that it is mental relaxation in the sense of absence of activity and tension. Desire and the subsequent goal-setting are about actively engaging in a mental activity, and thus they are a kind of opposite to relaxation. Figuratively speaking, just as muscular activity prevents physiological relaxation, wanting is the opposite of mental relaxation in that it relies on specifically activating certain computational processes. If you set the goal that you don’t want anything, you would actually be just setting one more goal, and increasing mental activity—this is another viewpoint to the paradox we just saw. But if instead, you learn to relax the planning and goal-setting system so that it simply rests, and does not set any goals and does not plan, then you resolve the paradox of wanting not to want. Furthermore, you can relax the evaluation mechanisms that compute frustration. Learning such relaxation is not easy, but the training methods discussed in this book were basically all designed to lead towards such a mental relaxation.17

The ultimate goal of Buddhist training is called nibbna or nirvna, depending on which ancient Indian language is used. It is defined as a state devoid of any suffering, the cessation of all suffering. The term literally means extinction, as in a fire being blown out. It is often described in negative terms such as “unconditioned”, “unconstructed”, or even “unborn”, which may sound nonsensical. I think the key to understanding this is that nibbna is reached by reducing, and ultimately removing, various mental phenomena, in particular desire; it is not about constructing any new mental phenomena. This may again sound paradoxical to any beginning meditator struggling to maintain even a tiny amount of concentration, but I am of course talking about highly advanced stages of practice here. Thus, the best description of the ultimate state may be entirely negative, in terms of what it is not, and what it does not contain.18 It is often described as freedom, and in particular it is freedom from those elements of the mind that produce suffering.19

One might think such a mind-state with no contents must have neutral valence, and could even be boring.20 Yet, Buddhist philosophy claims it is extremely happy and pleasant, in fact pure bliss. It is claimed to be the only thing that is not unsatisfactory in any way. This may perhaps be understood if we consider the mind in such a state to be completely empty, and we have seen that even a relatively empty mind seems to be, for some reason, quite happy.21 Nevertheless, we find yet another interesting paradox: How can having a completely empty mind possibly be pleasant since it logically should not contain any pleasure either? I will not try to resolve this paradox, which seems to reach metaphysical depths; let me just quote Sriputta, one of the closest disciples of the Buddha, who put it very simply:22

Just that is the pleasure here, my friend: where there is nothing felt.